Global Education

Caroline Robbins|News|December 5, 2018

photo obtained from Google Images

Throughout history, the world has become increasingly interconnected in relations between nations and their citizens to prosper, and the education of their people is one of the factors contributing to global success. When looking at education from a global standpoint, there is a question of how the United States measures up.

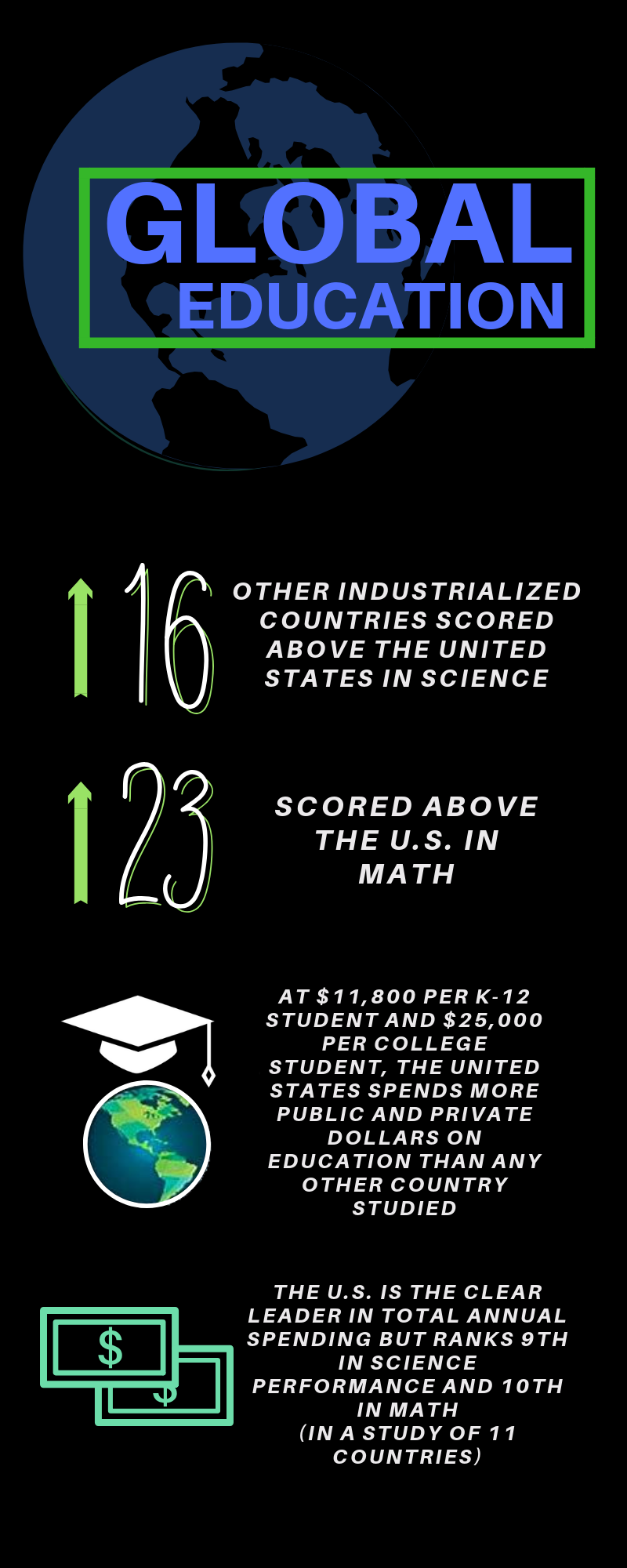

Recent cross-national testing administered by the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is showing the U.S. no longer leads the world in education, surpassed by other nations such as Finland, Canada and Singapore in math, science and reading. According to the test, which measures these three skills among 15-year-old students in 71 countries, the U.S. has only maintained remaining in the middle of the pack, never striving for top placement and making sure not to end up on the failing end either.

With statistics such as these, students attending American high schools, including Stanton, are not on par with their global counterparts. These gaps in skill could be the result of differently structured systems established in other countries, which offer students advantages in learning.

infographic by Zachary Genus

One of the main differences between these systems and those of the U.S. is the option of choice or specialization. American schools are required to teach a certain number of subjects and students are limited in their options for electives, whereas styles similar to the Canadian education system mandate education from kindergarten to twelfth grade while allowing students to pick their course of study. Due to the varying laws of each province, there is no national curriculum to group all students into a singular mindset, deeming certain skills to be relevant and others not, so each decides their own academic standards with each individual being allowed to choose certain classes based on the field in which they wish to find a career. Trade skills are offered for those looking to delve into the practices of the workplace, while tracks similar to Stanton’s International Baccalaureate and Advanced Placement programs are offered to those who are primarily seeking a higher-level degree. A clear impact is seen as a result of this process, as Canadian students placed seventh in science, ninth in mathematics and third in reading during the PISA studies. There is an exception in Quebec where, in high school, which they call secondary school, the mandated study ends at eleventh grade and the students seeking a career with a college degree must complete a two-year program known as “Collège d’enseignement general et professionel (CEGEP).” Despite this exception, there seems to be success for those allowed to choose rather than being forced to take certain courses.

Like Canada, Singapore places a strong emphasis on educating students rigorously in what they choose to study. According to the Singapore Ministry of Education, “Being able to choose what and how they learn will encourage them to take greater ownership of their learning.” Students are responsible for learning how to manage their futures by being encouraged to look into themselves and see where they believe they would best contribute their talents to society. Paired with their placement at the very top of the list, ranking first in reading, science and math, their approach appears to be effective.

Finland’s education system shares in Canada’s success while noting two other prominent contrasts with the American school system: competition and respect. Students at competitive U.S. high schools seem to constantly hear big names such as Harvard University or the Massachusetts Institute of Technology when testing season approaches, while Finnish students care more for the quality of the education rather than the name of the school they attended. Most schools in Finland are public, and the few private schools are often funded by public dollars. Teachers are encouraged to develop their own tests based on their students and their curriculum rather than accepting a standardized assessment administered to the whole nation. They value free time and assign less homework to allow their students to better understand the world around them, not just the world in a textbook or test. Their emphasis on a teacher’s role in learning proves the second key difference, which is how teaching is considered to be one of the most respectable jobs in Finland, and teachers are constantly being provided with new research and are prompted to perform their own experiments to fully understand what they are teaching their students. Through this encouragement of innovation, Finnish students develop a stronger sense of a work-life balance. These skills are not traditionally addressed in U.S. curriculums, which remains standardized with set learning programs for teachers.

photo obtained from Google Images

Stanton’s culture centers around the success of the students and it is nationally ranked due to its extensive testing and college level classes. However, trade skills are not offered as classes, and students, although given the option to select electives, are often faced with extra AP courses to boost their grades or provide them with more college experience. This can limit student exposure to other career paths which their international peers may have already discovered. The IB Program offers students the opportunity to have their work graded by other countries’ standards in hopes to expand their education to receive the same experiences and to be more prepared for integration into global society.

As the world continues to progress in its complexity, the need to train future generations to handle these changes becomes more noticeable. While no program can be completely perfect in preparing students for the challenges of an ever-changing world, considering or participating in the teaching styles of other nations can provide insight valuable to understanding the international community and its ties to each individual. The U.S. has yet to reach the top of the lists, but it can learn from the examples set by other nations, prompting its future generations to succeed.